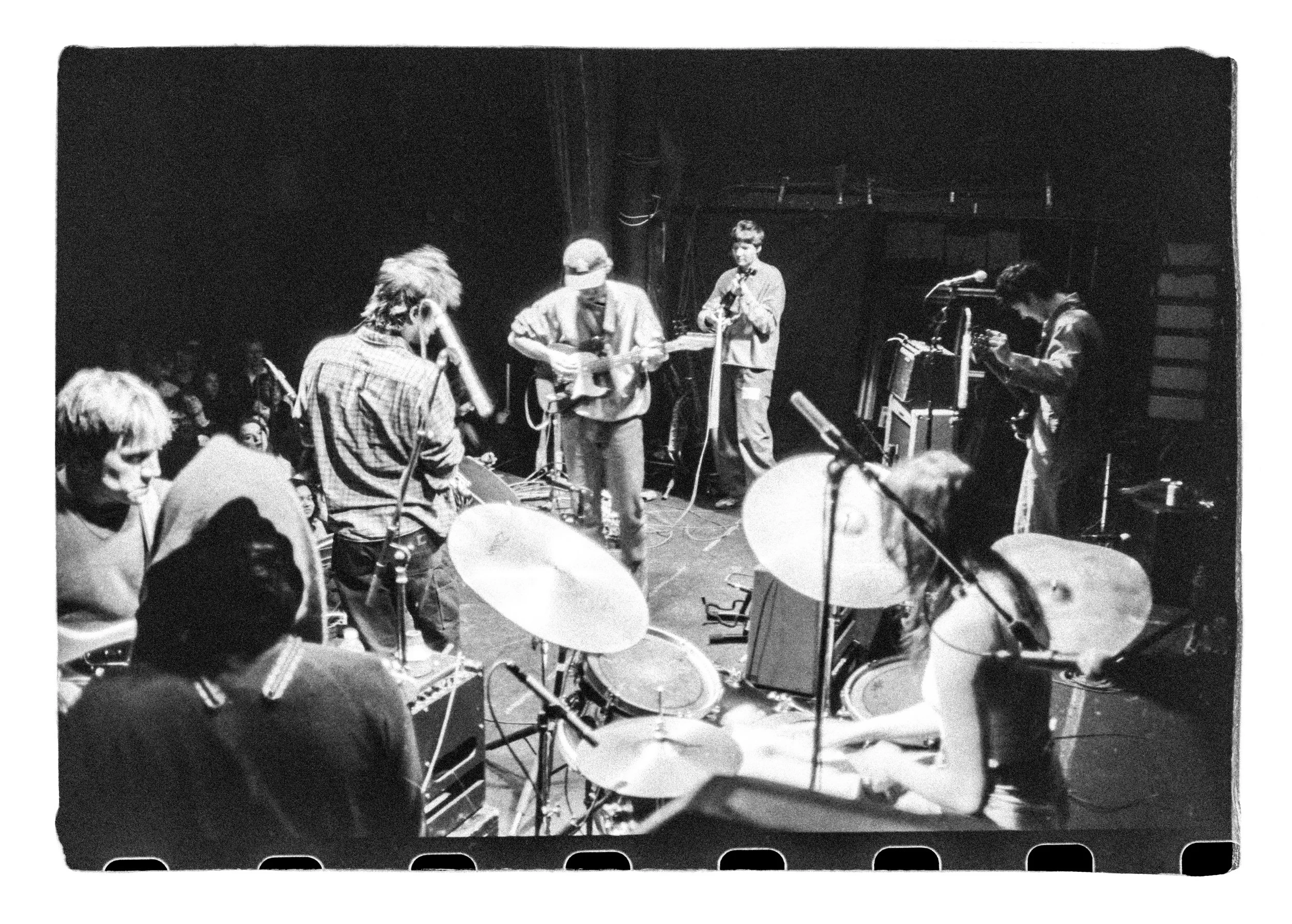

I got to the venue and immediately understood that winter was not done with us yet. It was cold in that way that makes your teeth feel involved. I stood outside waiting for Anna, stamping my feet and trying to remember why I ever thought carrying so many cameras in February was a good idea. She let me in just as the band was walking onstage to start soundcheck, which felt like slipping into a movie halfway through the opening scene.

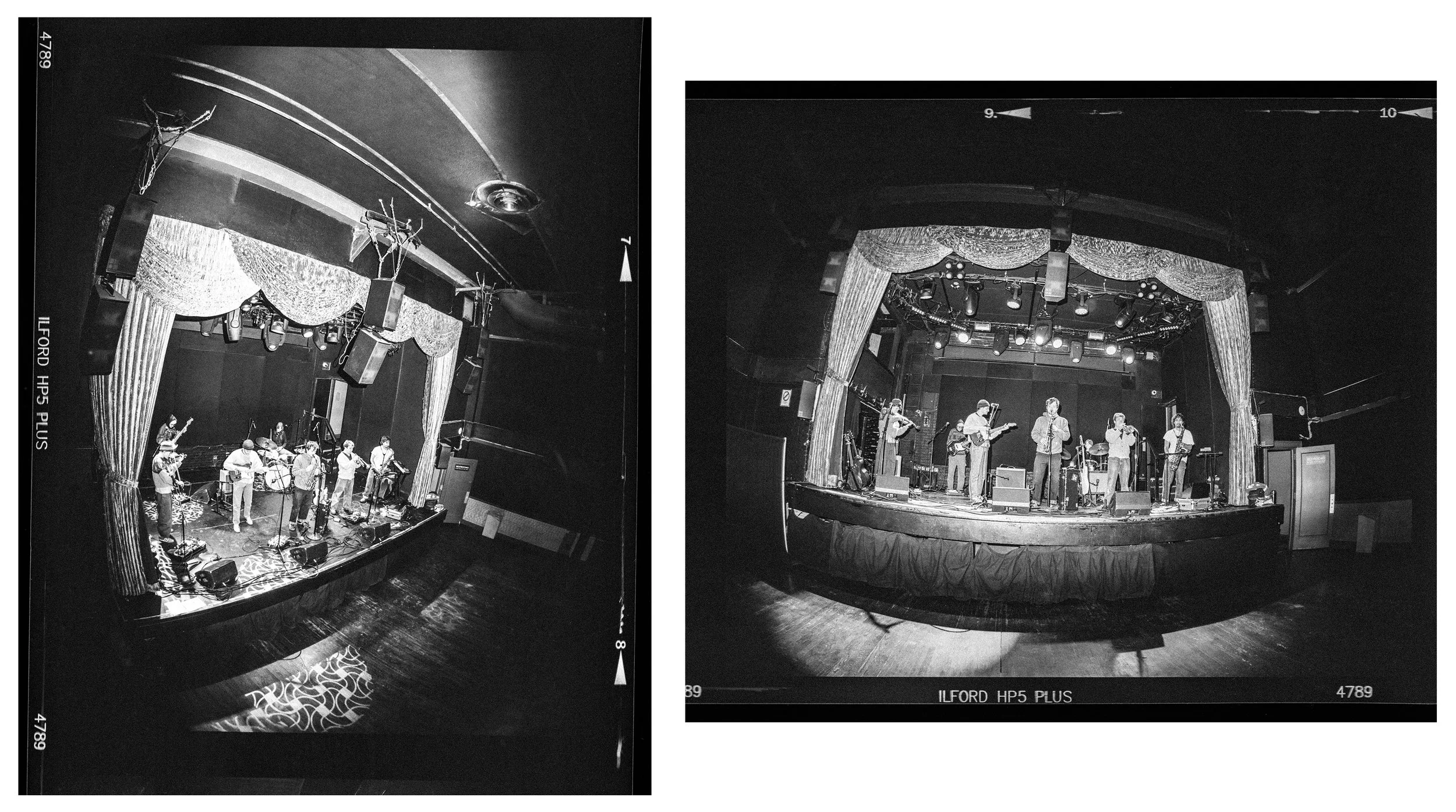

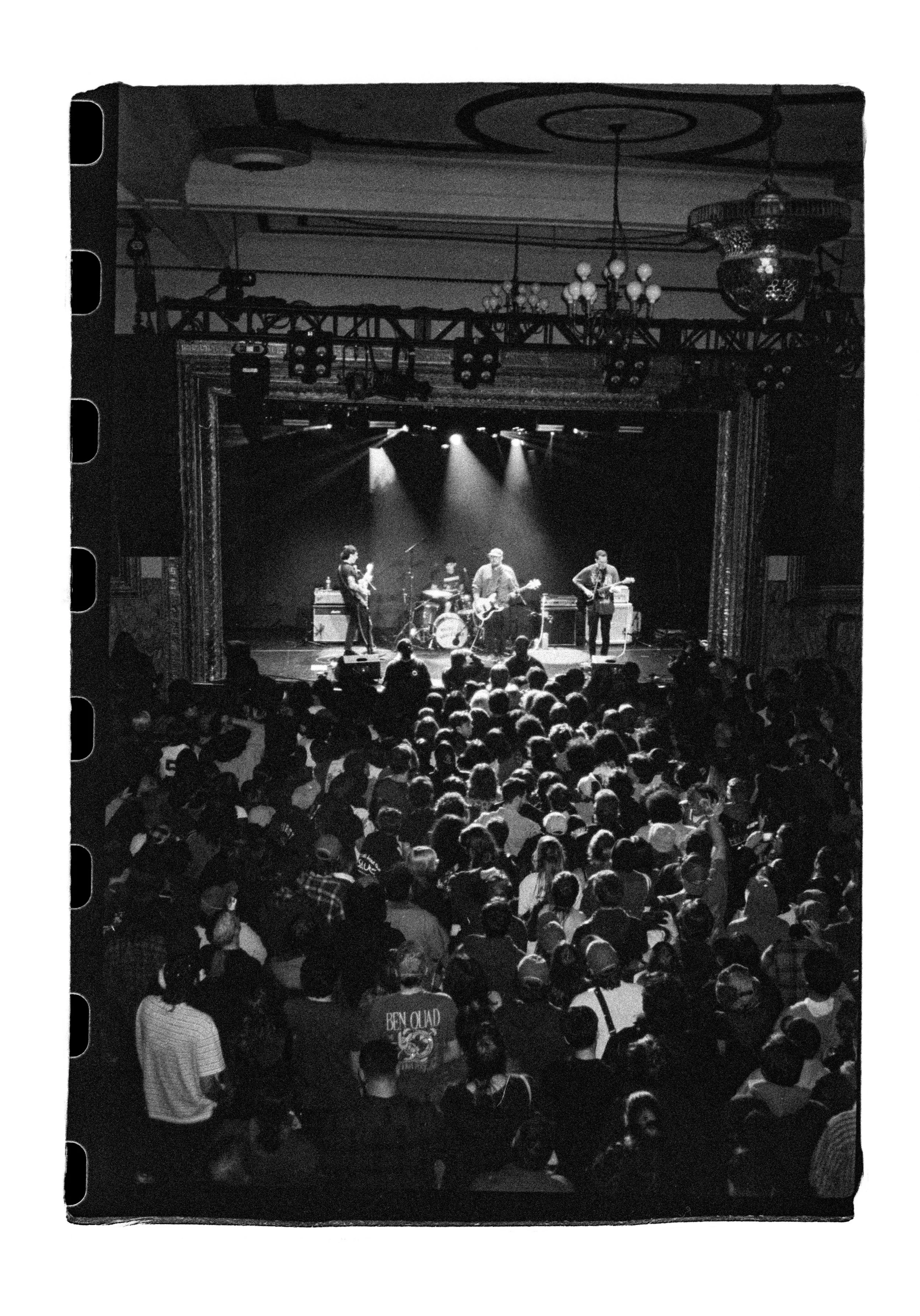

I dumped my bags in the green room, loaded a roll of film into the Pentax, hoping my fingers were still warm enough to work properly, and went straight to the stage to start shooting some test frames. I climbed up to the balcony, leaned over the rail, and fired off a few fisheye shots, trying to get a sense of how warped I could make the room before it stopped feeling honest.

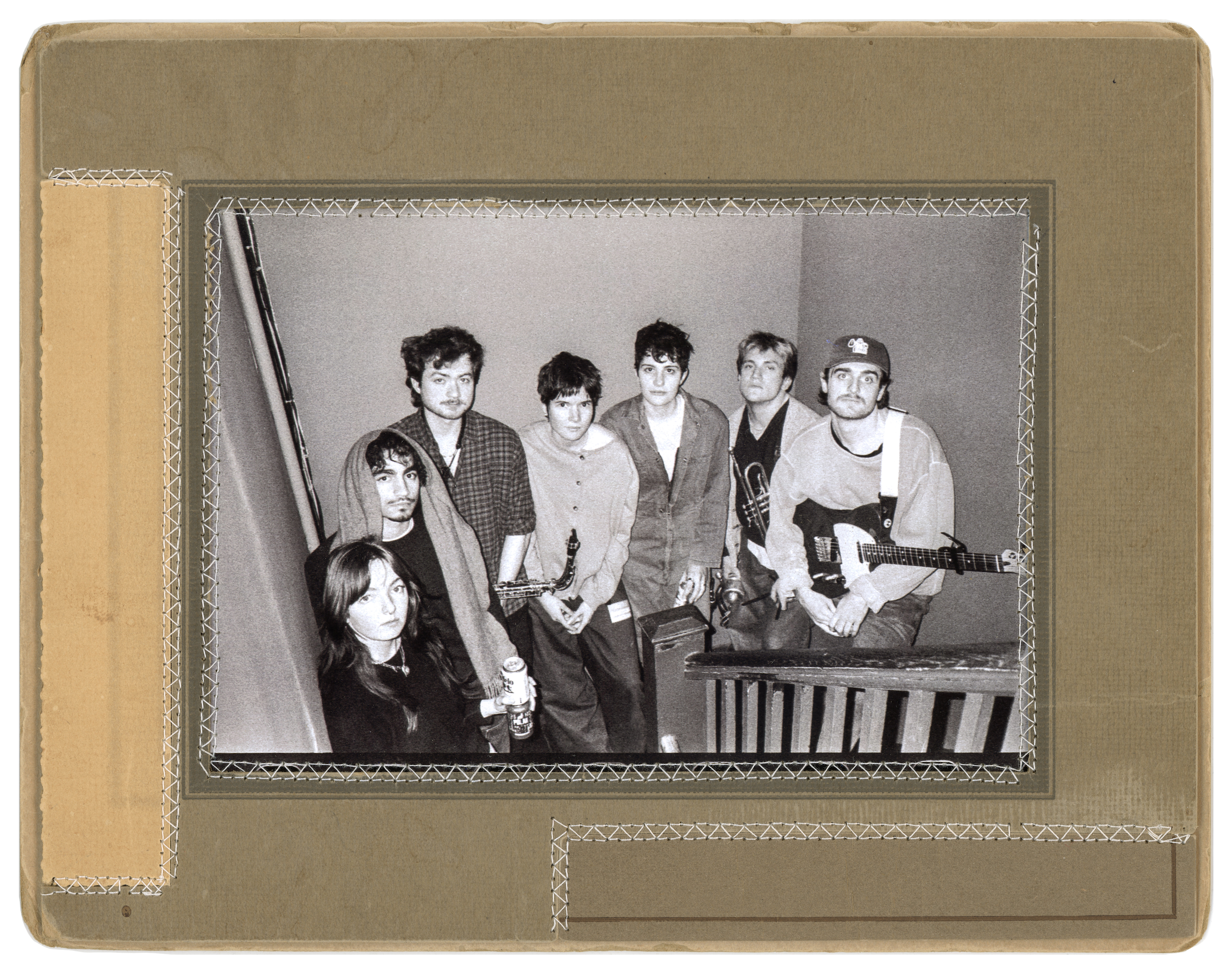

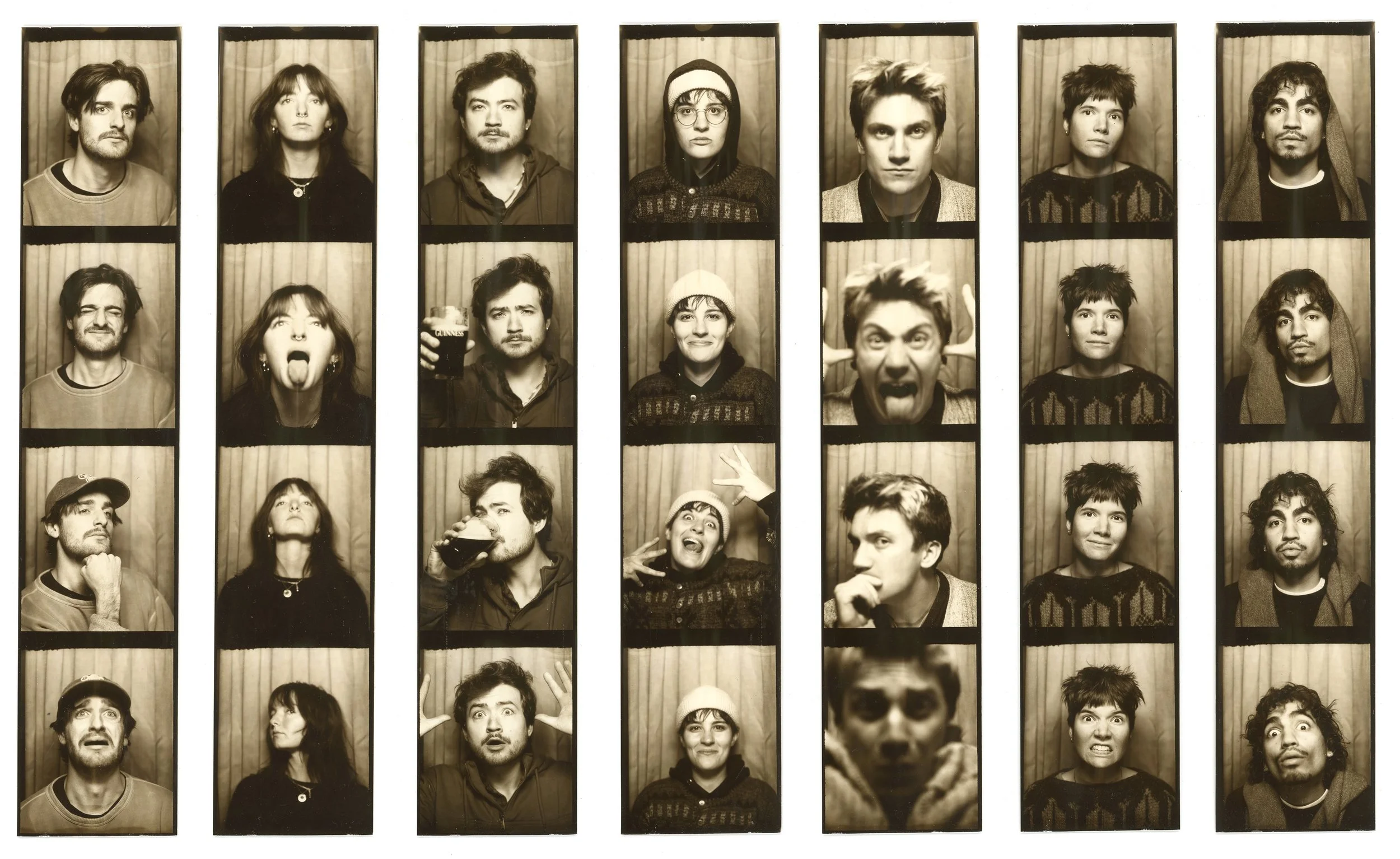

After soundcheck wrapped, we regrouped backstage and talked for a bit, nothing urgent, just pleasantries. At some point I decided it was extremely important that we go to a photo booth up the street, everyone agreed. Halfway there, we stepped into what can only be described as a winter puddle of unknown depth. Shoes soaked instantly. No going back.

We made it to the photo booth, did the thing, waited for the photos, and then found out the machine had jammed on the group before us. No photos. The band had already migrated to a bar, so I walked over carrying the bad news. That was when I noticed, with a mix of relief and disbelief, that there was another photo booth inside the bar right next to the venue.

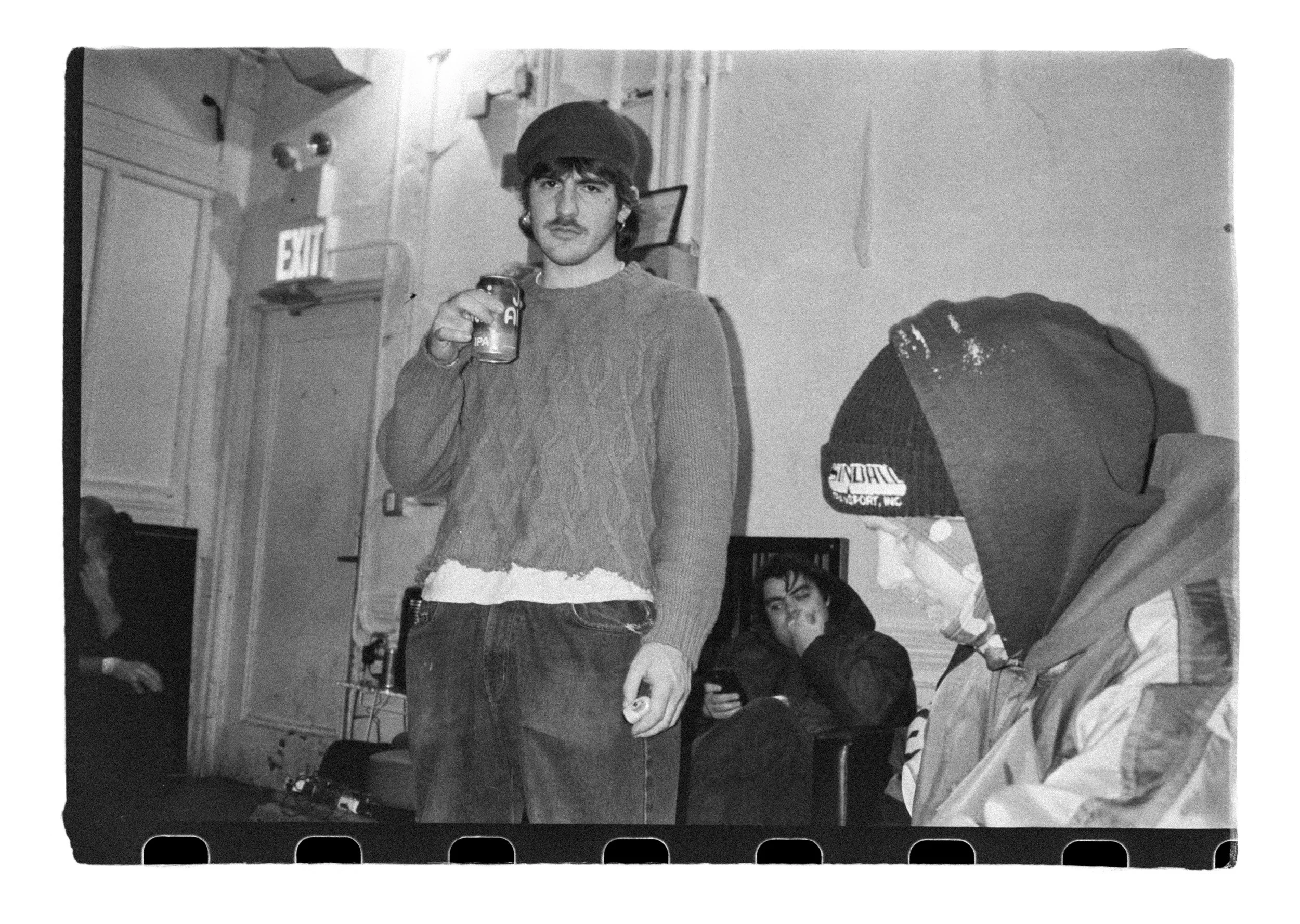

So I delivered the bad news, we shrugged, and did it all over again. After that, we went up the street and ate hot dogs like it was a necessary part of the ritual, then rushed back to the venue just in time for them to take the stage. Wet shoes, film loaded, night officially in motion.

Before sitting down for this interview, I reached out to Andrew Bishop, Chair of Jazz and Contemporary Improvisation at the University of Michigan, where the band first took shape. I asked him from his perspective as an educator, what distinguished Racing Mount Pleasant during their time at U of M, and how do you see those early qualities reflected in the band they have become.

In response, Bishop shared the following:

“Racing Mount Pleasant is one of the most imaginative groups of young musicians and students I have had the pleasure of witnessing in years. They bring a uniquely expansive perspective to music, drawing from deep folk traditions and far beyond, all brought to life by remarkable musicians from across a wide range of stylistic backgrounds.”

The decision to change the band name came after the album was already taking shape, and the name itself came from a misread highway sign. Once Racing Mount Pleasant became the name attached to the work, did it retroactively change how you heard the songs or understood what the record was holding? On a practical level, did that shift also change how you thought about presenting the band to new audiences versus people who had followed you as Kingfisher.

[Group] The name change did not change how we view the relationship to the music, or our outlook on the band or the album we were recording at the time. It happened during the end of the recording process and it gave us closure with the music we had been writing and recording over the previous 4 years. The name feels uniquely ours. We’re glad to have more people discover us under this moniker.

Sam, you have mentioned that on your very first day of college, within minutes of meeting Connor and Callum at orientation, you casually talked about wanting to start a band with a lot of people. Now, years later with two full albums behind you, How does it feel to look back at that moment knowing how real it became, and when you are writing lyrics now, do you ever think about that early version of yourself and what he was hoping to express before he even knew what the band would become

[Sam DuBose] Over this tour, I have thought a lot about how we have technically “done it”: we’re touring, we’re recording, we’re doing everything that a band tends to do. What’s interesting is that because this band wasn’t an overnight success, there hasn’t been a defining moment where it felt like I/we have accomplished anything drastic or life changing. Basically, it hasn’t felt like we have had our “we made it” moment. It’s been a really slow grind for me and everybody in this group to get to where we are.

During this January tour, we keep saying to each other that we can’t believe this is what we’re still doing with our lives after 5 years. At the risk of sounding cliche, it feels like nothing has changed and yet, everything has changed.

The lyrics I write are almost always about the people I know, or the situations we end up in. For the self titled album, we were essentially writing music about the scenarios surrounding us as we were making the album. I feel like with the self titled album behind us, we can finally move on from the life we had when it was being recorded. I’m really excited because honestly, it was a really hard few years for me.

And I think meeting Connor and Callum was one of the best things that has happened to me, as well as everybody else in the band of course, but they came a little bit after.

Early on, you said you were not wanting to be “entertainment for a party, but wanting to do more” and curate a specific experience for people in the room. Now that 3 years have passed and the new album has been out in the world for a little bit, I am curious how you see that idea today.

In practice, what does creating that experience actually look like for you now, and have any parts of that goal shifted or clarified as you have watched people engage with the record and the live shows

[Group] When we first started playing shows, we would sit down and have live visuals accompany what we played. The more we have continued and played larger rock venues, the quicker it became apparent to us that it wasn’t the most practical thing to put on in those settings. In the actual music, we definitely still aim for there to be intimacy. Someday, we would absolutely love to bring visuals back to our shows on a consistent basis.

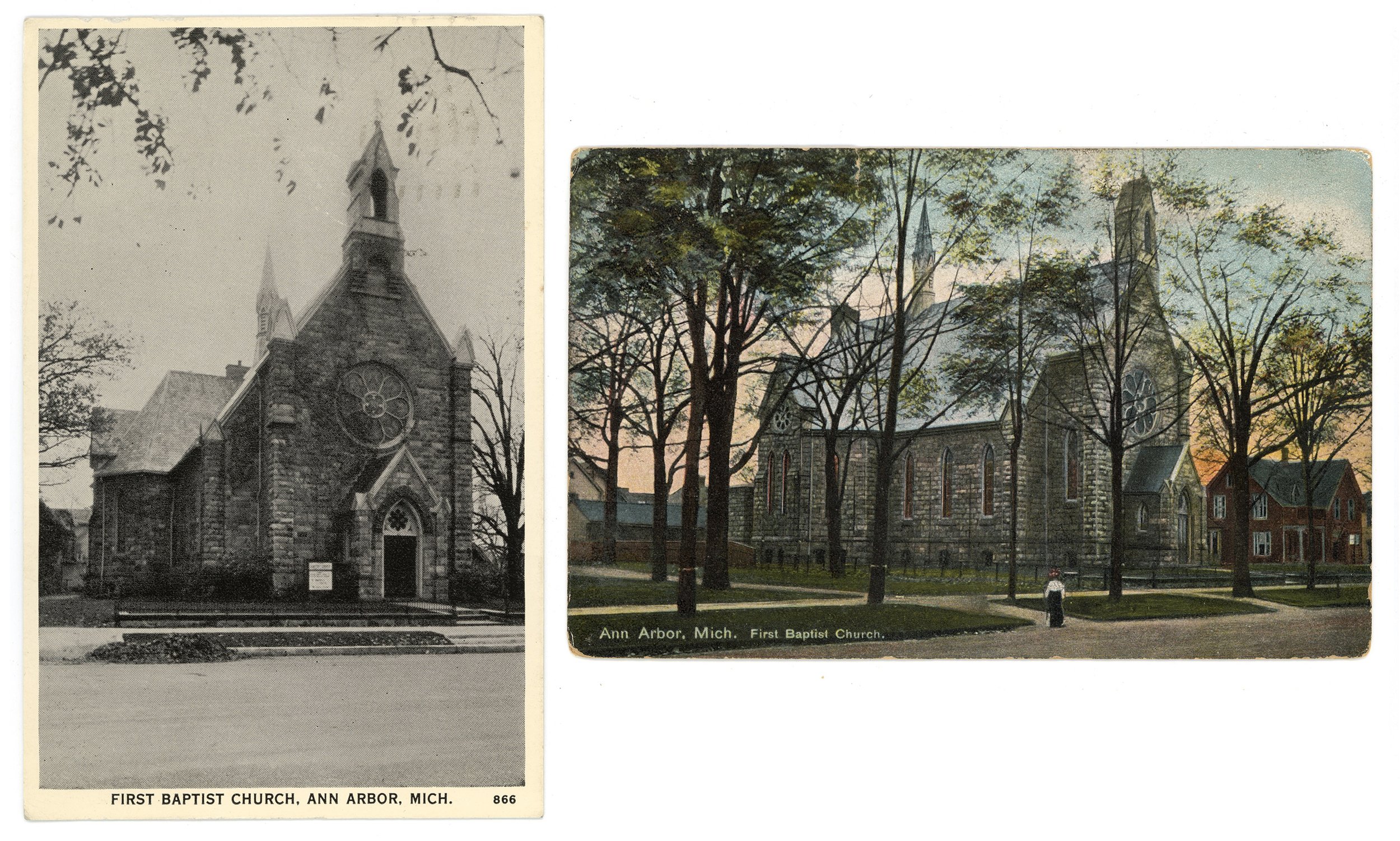

Some ephemera from the church “34th Floor.” was recorded in.

There is a strong collective feeling in the way the band operates, where the music feels like it belongs to the group rather than to any single voice. There are only a few bands that have really done that well, the group A Silver Mt Zion comes to mind, not in terms of a similar sound, but in how they function like a family. Other musicians or instruments can move in and out of that space and it never feels disjointed, it feels like they belong there as part of something larger. I am curious whether there were examples like that which shaped how you think about collaboration, trust, and making music that feels shared rather than centered on one person

[Group] It honestly happened very naturally for this band to essentially hive-mind our music, along with every aspect of being a band. There’s definitely a format that we follow when we work together. A vast majority of what we write now is as a group, and like everything that comes with this band, it’s a slow trudging grind to get anything finalized cause we all care way too much about what we do. Sam DuBose will bring in a song, or a lyric, or a melody, and the full group will finalize the sound/structure/parts of the song. We have not intentionally structured how we work together based on other projects. We essentially just ended up in a position where for better or worse everybody brute forces an idea and we end up with what everyone thinks is best at the end of the process.

Kaysen, you entered the band after first experiencing it from the audience, which is a rare transition to make. I am curious what it felt like to cross that line, from receiving the music to helping shape it. How did seeing the band from the outside influence the way you approached joining it, and for the rest of you, how did having someone who once stood in that room listening change the internal dynamic of the group, if it did at all

[Kaysen Chown] I remember very vividly sitting (slightly uncomfortably) on the basement floor of a mutual friend’s house who was hosting the show and thinking about how this band’s sound really stood out from any other DIY college band I had seen. At that point I was a super senior in college, so I had 5 years under my belt of moshing to deafening college bands—which is totally awesome in it’s own right—but Kingfisher captured the attention of the room in a way I rarely witnessed in DIY settings. At that point Sam Uribe had already reached out to record strings on one of their songs (Regulate), so having the prospect of collaborating with them was really exciting. As much as I was impressed by the horn arrangements and accompanying visuals, in perhaps a selfish way, I was already starting to imagine some string arrangements that could take the songs to the next level—I’m thinking of Annie as a particular example. I didn’t expect the band to offer me a spot in the already quite large ensemble, but the first day of recording strings with the band later that week was such a good hang that it seemed like a natural fit.

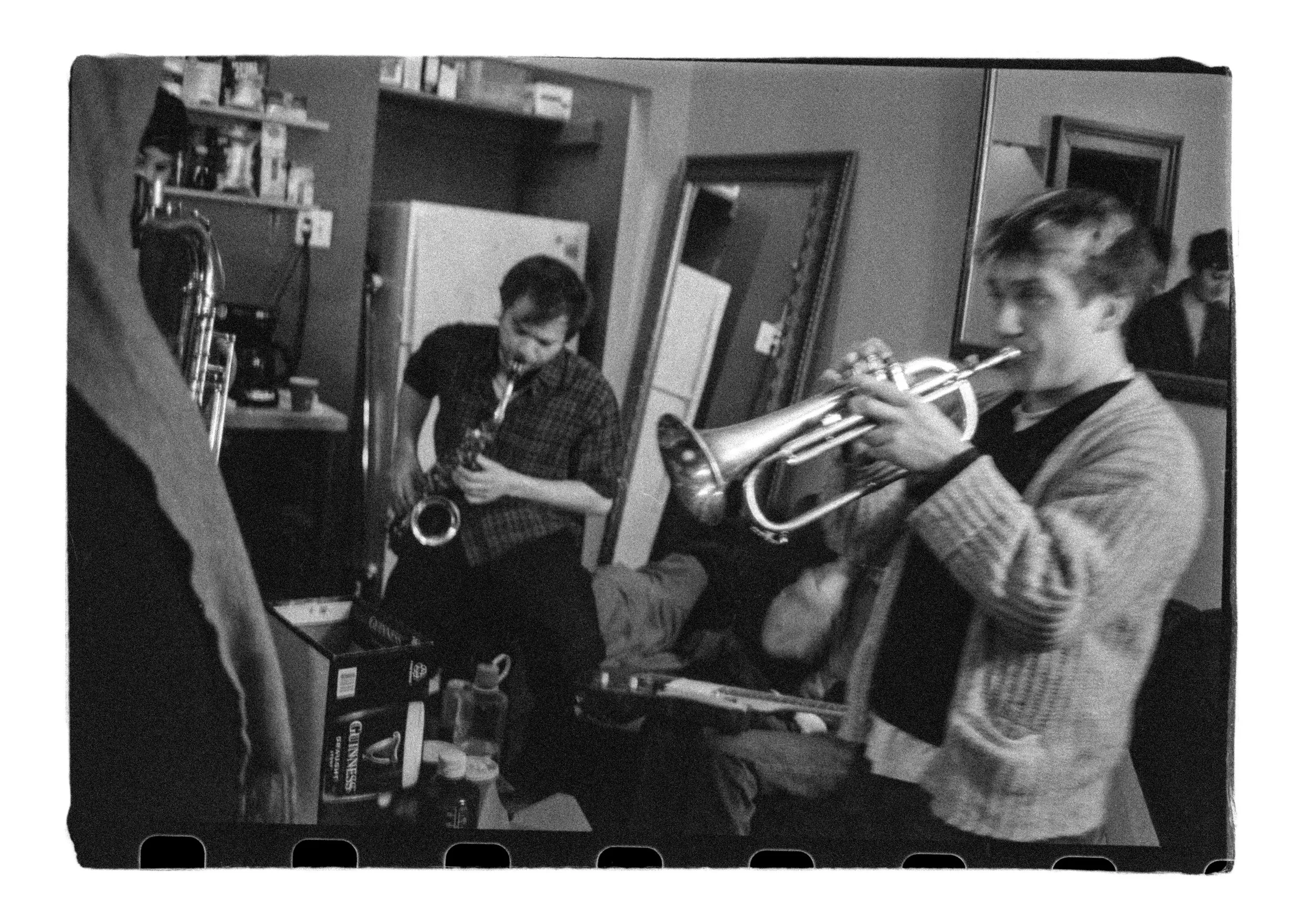

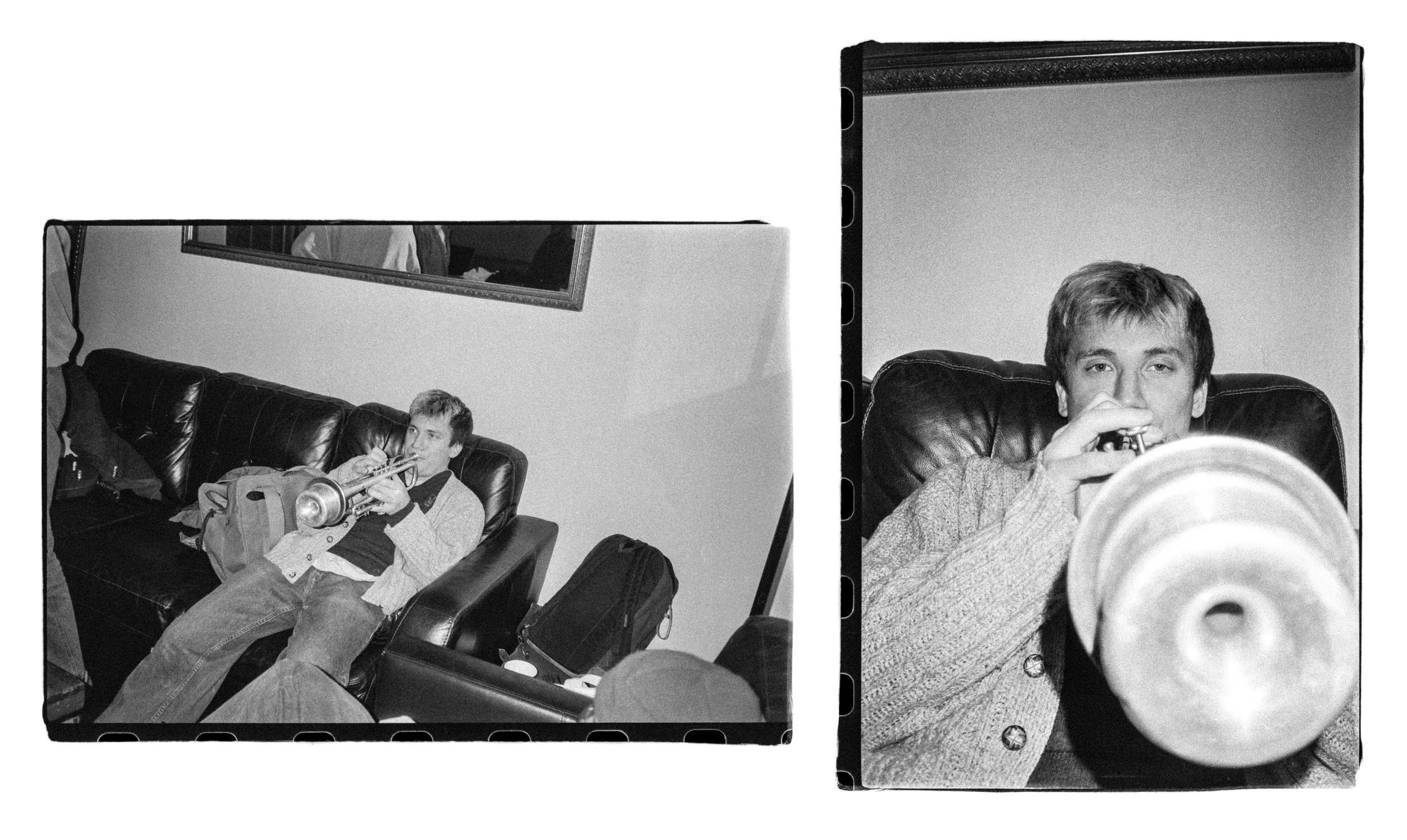

Most of you came into this band with formal musical training, especially in jazz, which gives you a deep technical vocabulary to draw from. I am curious how that background shows up in the day to day decision making. Are there moments where you consciously avoid doing something you technically know how to do because it would disrupt the emotional tone of a song. When you are writing horn parts, how much of that is written versus improvised, and how do those choices shift once a song moves from the studio into a live setting.

[Callum Roberts & Sam Uribe Botero] We’ve all spent countless hours developing our sounds and abilities on our instruments. For those of us who studied jazz, a majority of days and nights were spent practicing, and there’s some sort of inherent virtuosity that comes from that. There’s never been a point where we have actively tried to add something technically challenging just to do it, and like you said, we often will purposely stray away from that to leave more room and allow for more vulnerability. That being said, as horn players, we always try to make any part uniquely its own, and try to have the horns function at least slightly differently on every song. Sometimes it takes the roll of lead/rhythm guitar - other times it fills a more traditional “horn” sound, but there is an active attempt to make it unique in some way on every song, and because of that, every now and then we do write some pretty technically challenging parts.

Almost every part I’ve written was improvised at first, and over the course of months or even years, one improvised part will stick, or gradually settle into a solid part that stays more or less the same. But both in and out of the studio, there is still a lot of improvisation that exists in most of our songs, and there are only a few parts that are completely the same every time.

Samuel you spent time serving as a caretaker for a church, which meant living inside a space designed for reflection & ritual. I am curious how being alone in that environment shaped your relationship to sound and silence, especially the way you think about letting a room breathe rather than filling it.

Churches also carry a long musical history through hymns and worship songs that are built on repetition, restraint, and communal feeling rather than virtuosity. Did being surrounded by that influence the way you think about pacing, harmony, or emotional weight in your own writing, and do you see any quiet relationship between that world and the way Racing Mount Pleasant approaches melody and repetition

[Samuel Uribe Botero] I grew up in a catholic household, like many other Latinos. My living situation during college was very circumstantial, as the room I found myself in was passed down to me by a friend (I am not personally religious). I did however play in a few churches when I was growing up, which had some influence for me, but as far as living in this space, it’s hard to gauge how much of a direct influence it had on my musical choices. I’ll admit there were nights where I would go into the Sanctuary, where the mass is held. It’s a beautiful room.

We ended up recording 34th floor in there. Maybe you can say the acoustics of that room shaped how that song came together. Or maybe not. Spaces of worship are acoustically designed for a link between perceptive and emotional resonances, so in some unintentional way we may have brought that link into our recording choices. We also recorded some live takes of unreleased songs and other projects DuBose and I worked on a while back in there. I would love to put on a show there someday.

There’s a shared communal experience that happens when we play together. Allowing for the right voices to shine at the right time comes with a lot of restraint when you’re in such a big group. That, more than anything, has taught us about letting something to breathe and grow naturally. Maybe it’s intrinsic to communal music or maybe we borrowed those musical choices straight out of hymnals without realizing, but the intention of repetition etc. is all for the music to work as best as it can.

You have talked about memory as something that shapes the album rather than a straight narrative. When you write, are you more interested in preserving how something felt or conveying what actually happened

[Sam DuBose] Some of the songs, Call It Easy, Emily, Seminary, etc, were written even before our first album was released. Those songs kind of became some of the pillars of what would make up the self titled album. The meaning of those songs have definitely changed after writing and recording the rest of the album. So I would say that specific memories associated with that music isn’t necessarily important. It’s the way that those songs have essentially been playing in the background of my/our lives for five years. We have all personally changed so much, but those songs have mostly stayed the same. So I think our outlook on them is the biggest thing that fuels this loose concept of memory. Songs that were written more recently that ended up on the album will refer back to moments from those earlier songs.